Distelfinks and Dinosaurs

Illustrations: Jan Ratcliffe

Date: May 2013

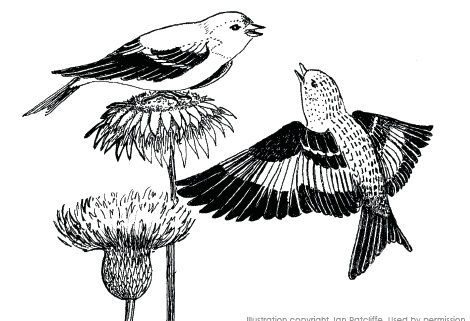

Sparrows don’t quite do it for me: I look at them and I clearly see birds, normal birds, hopping on the ground looking for seed or flying around. But distelfinks are different. Distelfink, literally “thistle finch,” is a handy word still used by the Pennsylvania Dutch for a group of birds that reminded them of the colorful finches of their homeland. It’s both memorable and descriptive, as distelfinks of all species adore thistles—in season, of course. Perhaps you’ve encountered flocks of pine siskins and lesser goldfinches raiding roadside thistle patches in fall, and fluttering wildly away as each car passes. For me, it’s less trouble to say “distelfink” than to list all our yellow finches—pine siskins and American goldfinches and lesser goldfinches—and our pinkish-red finches—purple, house, and Cassin’s finches. Other birds never act like dinosaurs. Distelfinks do, at least at my house.

Scientists who study fossils have, of late, been trying to tell us birds are actually dinosaurs: watching distelfinks makes me a believer. Ounce for ounce, they must be among the most aggressive dinosaurs left alive. This is made apparent by their habit of congregating in mixed flocks for fall and winter feeding. After all, most of us get a little irritable in crowds. Pine siskins are the worst. As they fight for space at the thistle feeder in our yard, they hiss and spit at each other, flashing the yellow under their wings and adopting threatening postures. Sometimes I think firebreathing dragons are the true missing link between birds and other dinosaurs, the extinct ones.

All this aggression is presumably brought about by the survival value of simply getting enough food. Small birds come together in numbers because of the advantages flocking offers: better protection and a warning system for predators. Flocking also means more eyes on the lookout for good food sources, but you still have to get your share while dozens of your fellows try to get theirs. Picture the noon crowd at your local food court.

Fortunately, we have a lot of thistle patches around. Therein arises one of those conundrums of conservation. Plant enthusiasts are trying to eliminate exotic thistles; bird enthusiasts enjoy thistle patches for the many birds they support. Although we have a variety of native thistles, most don’t thrive quite the way foreign invaders like musk and Canada thistle do. Have we improved habitat for distelfinks by allowing alien thistles to spread unchecked these last hundred years? Yes and no. Native birds do have alternatives: pine siskins are aptly named because they pick at pine cones as successfully as at thistles; American goldfinches are equally happy eating sunflower or dandelion seeds. Although their numbers may have increased with new food supplies, I don’t think removing exotic thistles will drive distelfinks toward extinction.

Flocking, or perhaps we’d better call it herding, probably also provided similar advantages to some dinosaur species. Communal dinosaur nesting grounds in Montana remind us of today’s seabird colonies, substituting groups of 25-foot-long duckbills who return to the same place year after year to nest together and care for their young. A herd of these Maiasaura migrating from nesting areas to feeding grounds might foreshadow the long migrations our flying dinosaurs make today.

Flocking, or perhaps we’d better call it herding, probably also provided similar advantages to some dinosaur species. Communal dinosaur nesting grounds in Montana remind us of today’s seabird colonies, substituting groups of 25-foot-long duckbills who return to the same place year after year to nest together and care for their young. A herd of these Maiasaura migrating from nesting areas to feeding grounds might foreshadow the long migrations our flying dinosaurs make today.

I imagine the pine siskins as coelurosaurs: scrappy, ostrich-like dinosaurs who may have hunted in groups. Solitary eagles are more reminiscent of lone hunters like Tyrannosaurus rex. A small peregrine falcon may recall Velociraptor; both have a strike that is quick and deadly.

Paleontologists have given us a lot to think about with this bird connection. Just think—now you can study dinosaurs in your own backyard! Much of our understanding of the past must come from our knowledge of the present, because Nature still works much as it did during the Cretaceous Period. Even scientists use their imagination, and often reason from analogy as well as from hard facts. As the famous geologist James Hutton once put it: The present is the key to the past. So if you want to see dinosaurs at home, and speculate on Earth’s older inhabitants, you’re in good company. I should warn you, however, that the bird specialists have not yet fully accepted this new, closer link between dinosaurs and birds.

Because birds are ubiquitous and seem to be a harmless background presence, we don’t consciously notice how thoroughly they’ve occupied “our” world. When you think about it, they’re everywhere. In and amongst our supposedly dominant culture, birds as a group continue to thrive and still live a variety of lifestyles. They are, however, showing the effects of our presence and the pressures we put on them; too many are disappearing. Those earlier dinosaurs, in their heyday, must have similarly dominated their environment, and eventually succumbed, perhaps due to some similar pressure. May the distelfinks last as long.

Copyright © 2013 Sally L. White