On Golden Clouds

Perhaps city folks don’t notice, but few who live in mountains and foothills escape knowing when the pines are doing their thing, and this spring was certainly one of the obvious ones. We see pollen adrift on spring puddles, pollen gathered from the roof to collect in rain barrels, pollen like golden dust all over our decks–marking the tracks of squirrels that have passed. We may fuss at the inconvenience of this annual deposition, especially if we’re the ones that sweep up, and we may question whether all the mess is truly necessary. Along the way to your deck, though, aren’t there a few compensations?

Pollen of pines and other conifers appears in great golden clouds loosened by spring breezes to drift and swirl across mountain landscapes. A combination of events makes this special sight possible, and you ought to consider yourself lucky to catch it. The dark green background of conifer dominance gives these seasonal clouds their dramatic visual setting, surprising newcomers and delighting residents with a familiar, yet mysterious, phenomenon. Probably there are other golden clouds—of grass, or cottonwood, or willow pollen—destined to remain invisible only because they lack the necessary dark backdrop to display themselves effectively.

The air is so filled with this evidence of male energy taking wing that even the evening news begins to notice. When mentioning pollen, does the weatherperson report that this massive outpouring ensures future generations of Colorado’s forests? Not so. Too often we take the presence of airborne pollen to be yet another inconvenience. But look at it from the other point of view for a moment. Perhaps the pollen grain finds it inconvenient to be forcibly snuffed up into a foreign and inhospitable land—our noses—where its germination processes can’t possibly aid the procreation of its species and can only annoy our own. Far from its intended destination, the inhaled pollen grain attempts to initiate a pollen tube on the moist surface of our nasal passages, chemically eating its way through the tissue, much to our continual discomfort.

Had the errant grain landed on a more hospitable surface, sifting down between the scales of a developing female pine cone of the correct species, its life would likely have been longer and more productive. The successful pollen grain spends the entire summer growing a pollen tube—dissolving its way through the soft tissues of the female cone. During the winter it is dormant, its growth arrested by cold. A new surge of growth in spring brings the tube within reach of the developing egg, where it deposits a sperm cell about 13 months from the time the original pollen grain left the parent tree. That’s a substantial lifespan for a single cell, and just the beginning for the seed that’s to mature in fall. But surely only a tiny fraction of pollen grains enjoy such a fate.

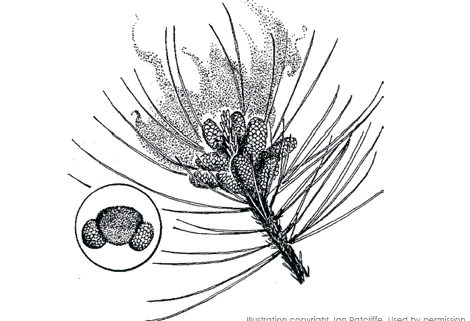

What good are all those unsuccessful grains? Besides the allergy-annoyance and resultant boost to the pharmaceutical economy, pollen grains collectively have plenty to tell. Carried by the slightest breeze and its own bladder-like wings, pine pollen spreads far and wide—in space and in time. Its abundance and resistance to decay make it an important fossil marker. Fossils and fossil pollen closely related to our pines have been found in Colorado from rocks deposited in Cretaceous time, as much as 100 million years ago. Other fossil conifers—and their typical two-winged pollen grains—date to the Carboniferous Period, some 300 million years ago. The distinctiveness and widespread occurrence of this pollen type have made it useful to us in another way—as evidence of past climates and environments. Pine pollen, for example, is regarded as an indicator of warm, dry climates, and is used extensively to document the comings and goings of glaciers during the last million years.

Pollen chronologies ought to be unreliable. After all, pollen can be carried far above the Earth on air currents, or it can be washed into rivers and transported out to sea. So far from its source, it may not be telling us what we think. You would expect strong winds and varied source environments to create an incomprehensible mix—a regional pollen stew from our golden clouds. The wide dispersal of wind-borne pollen surely blurs the distinctiveness of the record it creates. Despite such concerns, pollen dating works—ask any oil company who has profited by trusting the usefulness of this tool.

Copyright © 2014 Sally L. White

Illustration by Jan Ratcliffe