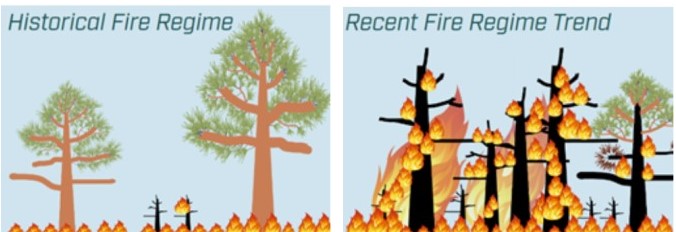

HISTORICAL versus CONTEMPORARY WILDFIRES

Wildfires in the mountain west have become less frequent but more intense.

Recently, the Denver Gazette published a short article on current research comparing historical versus contemporary wildfires in the America Southwest, with (to this reader) some rather surprising results.

The areas investigated in this study were primarily dry conifer forests dominated by Ponderosa pine and Douglas fir, very similar to our own forests in the Jeffco Front Range. Prior to 1880, wildfires used to sweep through these forests every 10 to 12 years. These were almost entirely low-to-moderate intensity fires that cleared out undergrowth and forest duff, burning off the lower limbs of the trees, but not devastating enough to kill the trees themselves. Typically, these low-intensity burns involved smaller areas, 5 to 250 acres. Despite the small size of these wildfires, the frequency and style of these fires were able to maintain forest health, even during prolonged periods of drought, when fires were started by lightning strikes and/or Indigenous forest stewardship events.

Fast-forward to the end of the 19th century and the incursion of Anglo-European colonialism, and the prevalent mindset of preventing or limiting forest fires. This allowed for the buildup of dry fuel on the forest bed and the overgrowth of the forests themselves. The wildfires we’re seeing today are tree-killing, high-intensity crown fires that sweep through hundreds of thousands of acres, irreversibly altering entire ecosystems and destroying entire neighborhoods.

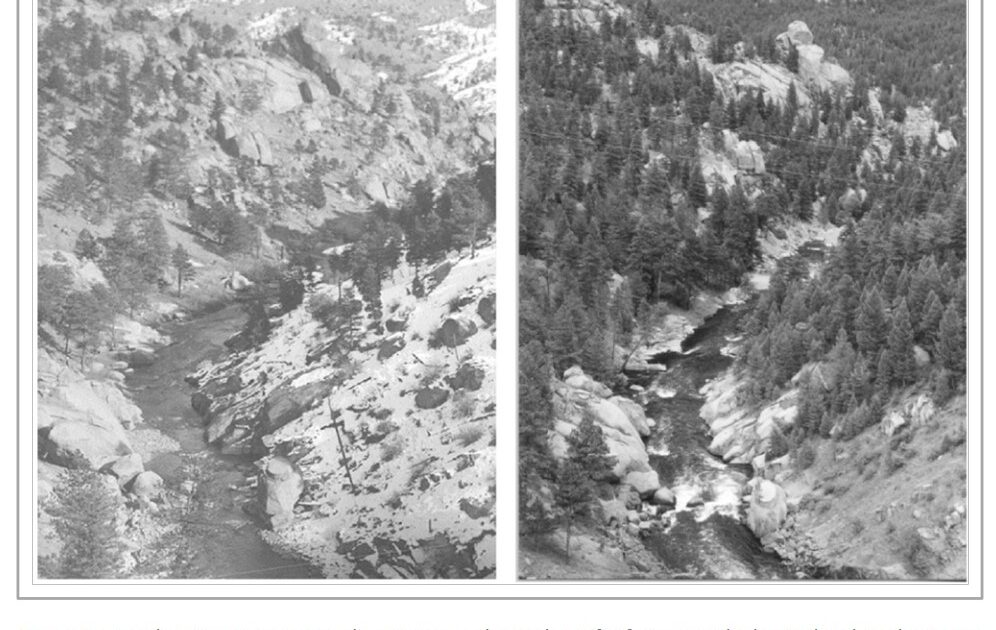

Comparison of Ponderosa pine forest, 1903 to 1999, courtesy of TogetherJeffco CWPP

There appear to be two prevalent schools of thought regarding the severity of historical wildfire. One school, which draws from the General Land Office surveys, is of the opinion that high-intensity, tree-killing wildfires have always been and still are part of our western ecosystem, thereby negating the benefits of forest tree-thinning. However, recent studies are showing that these high-intensity wildfires that devastate the ecosystem, sterilizing the soil and preventing the ability of the forest to regrow, are something that has come of age since the 20th century.

Tree-ring analysis is irrefutable evidence of fire frequency, severity, seasonality and extent. These records extend over centuries, for the life of the trees. Satellite observations and on-ground field observations, collected since the mid-1980s, are used to characterize modern-day wildfire intensity and outcomes.

A comparison of the two techniques shows that contemporary wildfires, tracked since the mid-1980s, are burning less frequently but with greater intensity than the very frequent, low-intensity fires of the 1700s and 1800s, and burning hundreds of times more acreage today than yesteryear. To sum up this situation in a few words, “The hotter the burn, the greater the kill”.

The bottom line: the fire regime in our Front Range is changing, and it’s changing our ecosystems. What used to be is no more, and we must adapt ourselves to the reality of this change. The study concludes that prescribed fire and controlled burns are really the best method to bring dry conifer forests back to a healthy state, but in today’s Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI), that’s not a practical methodology. The second-best method is tree-thinning (mitigation), and that’s what is happening in many of our Open Space parks today, especially those that are adjacent to human habitation.

If our forests are not thinned, the massively dangerous wildfires of today will cripple the ability of the land to regenerate the forests, and in the process, they will destroy entire neighborhoods.

Left to right, low, moderate and high intensity fire damage, courtesy of “Contemporary Fires are Less Frequent…”

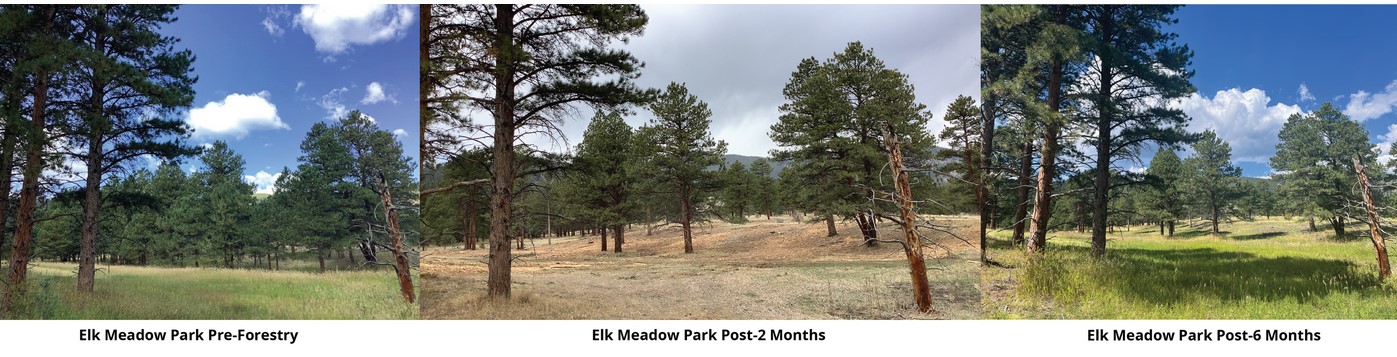

Many people who live in the Front Range, especially those who are under 60 years of age, have rarely if ever seen a healthy Ponderosa forest; they’ve only been exposed to overgrown forests. This is what they’re used to, so when they encounter a Ponderosa pine mixed conifer forest that has been mitigated, the difference can be shocking.

While many might protest that JCOS is “killing” our Open Space forests with their forest health implementation activities, the truth is that the Jeffco Open Space Forest Health plans align with both TogetherJeffco’s Community Wildfire Protection Plan (CWPP) and the current research referenced above. Our Open Spaces are adjacent to residential neighborhoods (or, rather, residential neighborhoods have grown up around our Open Space Parks), so there cannot be prescribed, controlled, low intensity burns without the threat of these fires getting out of control. The only other option is forest thinning. This may be hard to watch as it’s happening, but in the future the forest, including the forest residents, will be healthier for it.

Elk Meadow OS Park, pre- and post-mitigation, courtesy of JCOS Forest Management Plan

Meyer Ranch OS Park pre- and post-mitigation, courtesy of JCOS Forest Management Plan

Flying J OS Park, pre- and post-mitigation, courtesy of JCOS Forest Mitigation Plan

Want to dig deeper? Here are a few sources:

From the Denver Gazette: https://denvergazette.com/outtherecolorado/news/why-its-not-good-news-that-wildfires-are-becoming-less-frequent-in-the-american-west/article_f3661bd0-90b0-11ef-90a8-4b90c289a760.html

The referenced research article: https://www.nature.com/articles/s43247-024-01686-z

Contemporary fires are less frequent but more severe in dry conifer forests of the southwestern United States, by Emma J. McClure, Jonathan D. Coop, Christopher H. Guiterman, Ellis Q. Margolis, Sean A. Parks

What is a Fire Regime? A fire regime occurs in a particular ecosystem over an extended period of time. Scientists classify fire regimes using a combination of factors including frequency, intensity, size, pattern, season, and severity. Individual fires can vary greatly in severity, and the specific effects and risks caused by a fire will depend on the specifics of its fire regime. A classification system has been developed to describe the characteristics of a particular fire, determine which type of fire regime is common in a given ecosystem, and compare present fires with historical norms.” https://oregonexplorer.info/content/what-fire-regime

TogetherJeffco Community Wildfire Protection Plan (CWPP) 2024 Update, Wildfire History in Jefferson County, Wildfires prior to Euro-American colonization: “Wildfires and cultural burning heavily influenced Colorado’s Front Range before the era of fire suppression. Many Indigenous peoples utilized fire to steward the land, including the Cheyenne and Ute First Nations who hold much of the Colorado Front Range as their ancestral land (Wright, 2016). Frequent, low-severity fires were common in grasslands, shrublands, ponderosa pine and dry mixed conifer forests before European settlement in the 1850’s…”

Ponderosa pine mixed conifer species: Ponderosa pine, Douglas fir, aspen, juniper, white fir, Gamble oak

Typical elevation: 6,300 to 9,500 feet

Fire return interval: 7-50 years (frequent)

Fire severity: Low-to moderate-severity, with some smaller patches of stand-replacing fire where most or all trees die.

“Ponderosa pine mixed conifer forests are fire dependent. Historically, fire burned across the forest floor, controlling tree regeneration, removing lower limbs on mature trees, and creating large, open spaces between trees. Human management activities (grazing, logging, fire suppression) have resulted in unnaturally dense forests. During extreme weather, high winds can easily spread fire between tree crowns, resulting in very large high-severity wildfires where most trees are killed. This is not always the case but is a trend that has occurred more frequently in this forest type in the last few decades.” https://togetherjeffco.com/19989/widgets/88452/documents/61063

Jeffco Open Space Forest Management Plans and Current Projects: https://www.jeffco.us/3343/Forest-Management

Miss Mountain Manners wants to thank everyone who has taken the time to read this article, and especially those who have decided to dig a little deeper and educate themselves on forest health management. Our Western forests are not like the East Coast forests, which are thick and lush. Our Western forests are dry conifer forests that have adapted to our semi-arid climate. We need to respect that and follow in the footsteps of our Indigenous brothers and sisters, who understood how to properly manage them.

The post HISTORICAL versus CONTEMPORARY WILDFIRES appeared first on PLANJeffco.